That colossal wreck

A quarter-century gone, a rich man's ruins, and what remains

I’m not calling for more commemorating but didn’t it seem odd how little was noted on 2025 being the quarter-point of the 21st Century? It’s as if we can’t bear to reflect on what’s been and gone since 2000. So here’s an exercise: what’s the first memory that comes to mind from that millennium year?

My mind rebels, skips ahead a year. It’s a sunny September afternoon, and I’m home from college walking the dogs. Through wired earphones connected to a mini FM radio in the pocket of my shorts I’m listening to Steve Wright in the Afternoon, and as the dogs chase rabbits alongside Second Shaw (Dad had a name for every scrap of woodland) Steve pauses the show to tell us that an aircraft has crashed into a building in New York. In my mind, I picture some Mad Murdock’s spindly biplane crumpling on impact, deflected like a daddy longlegs off a candle, hardly a flicker.

When I force a rewind to 2000, this is what I get. Take one: a country lane beneath leafless trees, cold hands gripping the handlebars, and the shock, when I glance down, that the surface is glittering. What comes first, I don’t know, the catching sight or the letting go. The revs rise sharply as gravity loses its normal hold and the bike floats sideways beneath me. Just as quick, the tyre grips, the bike rights, and I breathe again, faster. Take two: seconds earlier, a spectacle glimpsed through the trees: golden domes glinting in the sun above a tangle of iron. The realisation that under the vast cage of scaffolding, there really was, about to emerge, the grandest palace built in centuries.

This is no Xanadu, no opium dream, and these are no pleasure domes; the proprietor has decreed instead a mausoleum. Bigger than Buckingham Palace but whose only purpose will be to house his and his children’s remains (though not their spouses’ – “no foreign blood”). Everyone suspects it’s another scam, a way to lock away his millions, but none of us foresee that it’s about to become Britain’s biggest mothball. The site – in its last days as an active building site as I pass it – is just outside Framfield, the village where my grandmother Billie lives, or lived. That’s where I am headed on my trusty CG125, in a break between A-level classes: I’m on my way to help Dad do up the bungalow while Billie is in hospital having tests after a fall.

Just before the turn-off to Billie’s is the churchyard where her husband Dobbie and several generations of our Bradford ancestors lie buried. The oldest of them, Thomas Bradford, has by far the grandest memorial. Of the weathered-away inscription you can still just make out that he died on 9th December 1883, aged 73. Between the angles of the tall headstone’s pitched top, his head is carved: bald on top, forehead lichened like Gorbachev, bushy mutton chops, prominent Roman nose – my father’s profile, unmistakably. Billie’s bungalow is a stone’s throw away; once you’ve passed the church, Thomas à Becket, it’s the next right turn, Becket Close. Dad is there already.

The palace as I glimpse it through the trees is as complete, as palatial, as it will ever be. Construction is faltering and will soon cease completely, either because Nicholas van Hoogstraten has fallen out with his architect (plausible) or run out of money (improbable). Picturing the state of it now, 25 years on, my imagination blooms with the decay – hairy ferns sprouting from cracks, basement lagoons, ivy-throttled pillars, and an owl that watches over everything from a dark corner. As I really still see it, though – from a distance, behind the KEEP OUT signs – it looks much the same as it did back then. And always it takes me back to 2000: the palace still emerging, the dome-christened new millennium still dawning, and the whole scene teetering on the threshold of ruin.

At around the same time, the owner of the palace made an appearance on our living room TV. Dad never missed the teatime news on ITV – shushing us into silence on the first note of the theme – and today’s local top story was a dispute between Hoogstraten and ramblers over blocked footpaths across the palace grounds. It was amazing to me that he’d agreed to be interviewed, but more amazing still was how brazenly he batted away fair questions. In place of answers, he reeled off insults: “Ramblers are perverts,” he sneered. “They’re anarchists… peasants… riff-raff,” by now he was warming to his theme and clearly having fun, “they’re the great unwashed… the scum of the earth.” I’d no way of knowing how my parents would react – though they wouldn’t have called themselves ramblers, they loved walking and regularly used footpaths – so had every right to take offence. But as I glanced over to watch them watching him, I’d rarely seen them so rapt. “He don’t give a shit,” said Dad, admiringly. “A tidy article, ol’ Hooky,” Mum agreed, as if referring to an old friend.

As for me, I knew I ought to feel appalled, but what I actually felt was something closer to my parents’ awed fascination. Everyone knew Hoogstraten was an amoral shark in business, but what did that matter if he was willing to entertain us? The glint in the eye, the guess-if-I’m-being-serious, camp bullyboy act was prime-time viewing as we’d never been delivered it. Here was a working-class Sussex man – judging by his accent – who was just like us, yet not like us at all. The difference being, he had enough money not to care, be it about rules, neighbours’ disapproval, accusations, anything. For us, just imagining having the gall to stick two fingers up to polite society, without qualms, was a kind of vicarious liberation. As he ranted, we took a joyride into fantasy – an indulgence that was about to catch like wildfire. To look back now and identify Hoogstraten as a forerunner of today’s populist showmen, the breakers that brought us Brexit and MAGA, might sound like the smart talk of hindsight, but it can’t be denied. We laughed along with his pantomime villain schtick while we still had a chance to recognise it for what it was, the essence of the coming age.

While workmen downed tools and walked off the job at the palace, Dad and I went into overdrive at the bungalow. Our first job was to get it clean. The smell of sugar soap still takes me back there; filling one steaming bucket after another, stirring in the pungent crystals, and scrubbing away at the waxy yellow gunge that coated every surface – 20 years’ worth of nicotine and kitchen fat. It was satisfying work, the wiping away of so much neglect, like archeologists exposing original surfaces. Once everything was dry, we crouched at a doorframe and Dad showed me how to paint with gloss: keying-in to let the new paint bond, loading the brush with just the right amount, catching runs. Usually he’d huff and tut at my nervous cack-handedness, but this time was different – he was calmer, almost kind, and it was a relief to be, for once, a help rather than a liability. In those few weeks at Billie’s bungalow we were, for the first and only time in our lives, a team.

I don’t know if Dad really believed his mother would recover enough to come home, or if the state of the bungalow had pricked his conscience, but either way it was important to him to make it nice for her. He drew the funds for the redecoration from her account, using his power of attorney to buy materials and pay me an hourly rate. Uncle Roger, who lived just down the road, took exception to this plan, and just like that the two brothers cut each other off. “Fuck him, I’m finished with him,” was how Dad opened and closed the subject. Not another word would pass between them for the next three years, until Roger lay dying from cancer – and even then, not many.

They will be forever linked in my mind, the two simultaneous feuds, one that stops the building of the palace, the other that festers silently, dividing Dad and his brother, as we work on the bungalow. They had been close all their lives – a bond consecrated in the spilled blood of their father that night in the Sixties when they finally snapped and beat the old bastard so bad that Billie ran down the road screaming. That’s something else Dad and Hoogstraten, both 1945 babies, had in common: a lifelong grudge against their domineering fathers.1 What is that mess of marble and iron now – frozen in the geological time of the rift like a great scab that refuses to heal – if not the world’s biggest monument to bad blood?

This is not what ruined palaces are meant to be. They are meant to be a tantalising remnant of grander times, evoking the scenes they once contained. “The ruins of palaces bestow a unique pleasure,” wrote Rose Macaulay in her 1952 book The Pleasure of Ruins:

“It is the haunting of past grandeur, the contrast between… the courtly life led in them, the banquets, the music, the dancing, the painted walls, the sculptures, the rich tapestries, the bright mosaics, the princely chatter, the foreign envoys coming and going… and now the shattered walls, the broken columns, the green trees thrusting through the crumbling floors. Fallen pride, wealth and fine living in the dust, the flitting shades of patrician ghosts, the silence where imperious voices rang, the trickle of unchannelled springs where fountains soared, of water where wine flowed. All this makes for that melancholy delight so eagerly sought, so gratefully treasured, by man in his brief passage down the corridor of time, from which, looking this way and that, he may observe such enchanting chambers of the past…”

There is no delight to be taken from the ruins of Hoogstraten’s palace, because it has no history and refers only to itself. It is the ruin of a ruin; its pleasureless domes decree nothing but look ye upon this man of measureless spite. In centuries past, those with too much spare cash would build follies in their gardens – faux-ancient temples or towers in miniature – furnishing their place in the grand sweep of history. It doesn’t have quite the same effect when the folly is not a feature but the whole thing: the man at its centre interested in only one history, his own legend. But as I write off the palace as a blot on the landscape, besmirching Framfield’s southern horizon, a voice from the graveyard interrupts.

“Wait,” Thomas Bradford seems to chide me, hoarse from lack of speaking, his stone face staring towards Framfield church. What is it, old man? And why are you buried the wrong way round? Most of the dead here lie with their feet to the east, so that on the day of resurrection they may face the rising sun – and, God willing, the risen Son. But Thomas’s headstone, unlike the rest, faces west, towards the palace. He was a churchwarden, I remember, and this must be the reason: when the day comes, he’ll be needed. This way round, he’ll rise alongside his Lord, facing the parishioners, ready right away to continue to serve. His stony stare towards the church betrays, it strikes me now, a doubtful pride – and reminds me that the church as he last saw it was so dilapidated it looked set to fall down. The tower had, in fact, collapsed two centuries earlier, its bells long silent on the church floor and rusted by the rain that dripped through the roof. When his time came in December 1883, Thomas must have died hoping, faithfully but without assurance, that a saviour was on the way.

Facing west as he is, it’s less than a mile to the palace, an easy walk, but what Thomas would expect to find there is not a ruin but a large, lived-in house: High Cross. He was acquainted with the proprietor, Robert Thornton, but he cannot have known the extent of that man’s plans for the church. High Cross was a manor house but not especially grand, and did not flaunt the fact that Robert Thornton was, by dint of lineage, a man of near-unlimited means. His great-uncle, Richard Thornton, a merchant of yeoman stock, was the sort of man Hoogstraten can only dream of imitating.

Audacious in business, Richard thrived when the stakes were higher than any normal man could bear. When, for instance, Napoleon blockaded the Baltic in 1810, Richard did not flinch: he armed his ships, sailed on through, and set about cashing in on other men’s caution. He died the richest commoner in England, leaving the largest fortune yet valued for probate – nearly three million pounds – a sum that, adjusted to today’s values, makes Hoogstraten’s haul look piffling. To his home village of Burton-in-Lonsdale Richard bequeathed a charity school and two rows of almshouses, while the rest of his fortune passed to his favoured nephew, Thomas, whose son Robert, the squire of High Cross, must have inherited his great-uncle’s sense of civic duty – because in 1891 he decided it was high time to rebuild Framfield church.

The full-scale restoration commissioned by Thornton included a new tower and cost – in today’s money – several hundred thousand pounds. Work had barely begun when, on 13 December 1891, eager to check on progress, Robert braved the cold and strode up the hill to the church. It would be his final act: he caught a chill, or so it’s said, and died the next day. Nonetheless, his intentions were honoured. His son Robert Jnr stepped in and oversaw the project’s completion. The tower was built, the bells hoisted, and to this day the Thornton legacy rings out across the village and over the High Cross estate – now dominated by an enormous ruin.

The Thorntons saw out two world wars at High Cross: Robert Jnr died an old man in 1947, his wife Charlotte in 1961, aged 95. Their era formally ended in the early-Seventies when the estate was bought by Cyril Newton Green, a former London publican, and his wife Shirley, who had scraped together the funds to set up a nursing home. The folly was not the plan itself, but their decision to involve in the financing a man entangled with a local tycoon who had recently been jailed for a hand-grenade attack on the home of a Brighton Rabbi. Getting wind of the purchase soon after his release, Hoogstraten hightailed to High Cross and rapped on the door, surrounded by henchmen. When it swung open, he declared: “This is my place.”

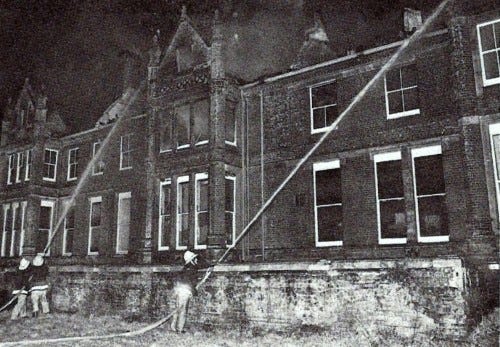

The Newton Greens promised to repay the debt, which for a while kept him at bay, but after Cyril died Shirley fell behind with repayments. Hoogstraten toyed with her like a wanton cat, initially feigning romantic interest, then growing bored with his own game. In June 1978, he pounced. Laying siege to the property in medieval fashion, he had his men block access with trenches, felled trees and barbed wire, and cut off the power supply. The rest home’s 12 residents, all over 80, were trapped for hours until a social-services minivan was scrambled to evacuate them. Shirley, who had rushed away to obtain a High Court injunction, returned to find her four dogs bloodied and whimpering in the back of her car, so savagely beaten that one had to be put down. It was over. There would be no recourse and no negotiation: Hoogstraten had taken High Cross by force. The house was boarded up and left to moulder until, in 1983, it was gutted by fire. Two years later, the burnt-out shell was levelled and into the ground beneath it were dug the foundations for a palace.

As I’m writing this in the closing days of 2025, news breaks of another fire at a property linked to Hoogstraten: this time a hotel in Hove, and mercifully it’s extinguished by fire crews without anyone coming to harm. I google the hotel and find a litany of angry reviews from people who lost deposits when it closed in 2020. One is titled “Cheated out of £1,000 deposit”, another “Goodbye to £600”. The Hoogstraten family shuttered several local hotels during Covid and has not reopened them since; hospitality, they seem to have decided, is not for them. More disturbingly, reports link the charred property to a missing-children scandal, with scores of youngsters said to have vanished from the hotel after it was repurposed to house unaccompanied asylum seekers. It is suspected, adds the report, that many were kidnapped and trafficked into slave labour. How has it come to this: a property-hoarding dynasty entrusted to shelter society’s most vulnerable, and profiting as it fails them catastrophically.

It could have turned out so differently. Hoogstraten has always had a soft spot for hotels, and as an upstart young investor he pictured himself as live-in host, kingpin among glittering guests, floating on envy and admiration day to day. Back then, he was still plain Nicky Hoogstraten – no need yet for the self-aggrandising “van” – and his dream seemed to be coming true when he snapped up a swanky 30-room establishment a few doors along from the governor’s residence in Hamilton, Bermuda. But how does a rough-hewn Sussex lad-done-good fit in among linen-clad colonials in their gin-clinking cliques? He lasted less than 24 hours: something spooked him in the night. “I was only 18 and didn’t know much,” he recalled decades later. “I felt like a fish out of water. I only stayed there one night [even though] it was my own hotel.” Whether this moment was the original injury or just one more affront, some deep part of him would remain forever that humiliated adolescent lost in a maze of empty rooms he can own but never inhabit.

Billie never returned to the bungalow, never came home to the surprise of new paint, bright surfaces. Too frail, she went directly to a nursing home and died a year later in summer 2001, away and gone before clear blue skies became indisociable from flame. Spared too the deaths of her boys, first Roger, then Dad, neither making old bones. Nor did she witness the nascent palace on her doorstep end up the wreckage of a runaway ego, rotting bait for tabloid clicks, AKA “the biggest slum in Britain”.

I don’t ride past anymore; my motorcycling days were ended in 2006 when an ophthalmologist condemned my retinas to a ruin of their own. Even so, there is no getting away from Hoogstraten around here. At least weekly I walk or cycle past the Tudor-arched front door through which Marilyn Monroe once passed, having turned up unannounced for lunch, as did a former Queen, who fingered the furniture vainly hoping to be gifted her favoured piece. The Shelleys was our town’s plushest hotel, but Hoogstraten acquired it in 2011, abandoned it in the pandemic and hasn’t touched it since. These days the whole building seems to slump embarrassed at what it has become, its window frames flaking, their panes dark except for security signs. In the glass an old scene might still flash, albeit more dimly now, and sadder for the memory of elegance.

Hoogstraten turned 80 last year, and you’d suppose he must be thinking, what has it all been for? Last autumn, as I was struggling to write this piece – that is, to account for the fact I couldn’t get Framfield’s unfinished palace out of my head – a media alert flashed up on my phone: Hoogstraten was back in the news. Had he died? No, quite the opposite: he was reasserting his presence. “Notorious billionaire breaks 30-silence on why giant £100m UK palace isn’t finished,” raved the Daily Express headline, impressively jamming at least four falsehoods into a dozen words. The story is fascinating in spite of itself, for what it reveals between the lines.

It takes place at a crummy Hove hotel, naturally, and the elderly Hoogstraten, chaperoned by his son Max, is a shadow of his dapper self, dressed as though he’s forgotten who he is “in a grey Karate Dojo gym T-shirt, trousers, and trainers”. He perches at a window, distracted by the trees outside, rambling about how he once sacked a gardener for over-pruning them. Worry not, the old bravado is still intact: he’s soon bragging about nearly throwing Martin Bashir off the scaffolding. But at 80, the nearlys are lifting heavy.

The article boldly promises to extract from Hoogstraten “the exact reasons why work stopped and what the future holds for the palace”. But what it delivers is King Lear minus the poetry: a muddled old man leaning on his obedient son to prop up his hubris. Both men “maintain with utter conviction,” the reporter assures us, “that the project will eventually be finished,” but just a sentence later Max admits, in a Shakespearian aside, that “it’s not on the agenda”. It’s a dangerous slip, hastily saved by flattery. “My dad has every intention to finish it, but he still works 16 hours a day every single day.”

As the old man mutters his old mantras – reminders of his capacity for violence, denials of violence he was convicted for – the journalist tries to fulfill the second part of his brief: accounting for why work on the palace stopped in the first place. Was it his conviction for manslaughter in 2002 or the breakdown of his bromance with Robert Mugabe? It’s no good; the time of objective fact has long since passed. “So much time has passed,” he writes, “it’s hard to know conclusively if it was the chaotic land seizures of white landowners in Zimbabwe or being accused of a terrible crime that took his focus from the palace.”

The interview winds down with Hoogstraten forecasting Armageddon – “the world is fucked” – and denouncing Musk and Trump, not for their fascistic tendencies but because they have been known to take out mortgages. To his feudal throwback mindset, the only real wealth is outright owned real estate, taken by force or intimidation but never by borrowing. Only a loser would take on debt and be dependent on another. He knows he isn’t in the same league as today’s feudal lords, who accumulate leveraged, algorithmic fortunes on a scale that makes his own seem quaint. He is locked out of their club, and so it becomes a vital distinction that their status is built on “bullshit” numbers on a screen, his on solid ground. None of those super-rich speculators have a ruined palace as big as his, not because they don’t want one, but because – and this is the quote with which the report smartly ends – “nobody has any real money anymore”.

Just as I’m beginning to hope I’m done with Hoogstraten, I stumble upon a video: two teenage lads filming themselves climbing through a window of the Shelleys hotel and taking us on a tour of the musty rooms – still full of furniture and fading decor. Owing to savvy editing, it has the tension of a thriller, opening with a teaser from the ending – we know they’re going to end up apprehended by police. Halfway through, the more studious of the two takes out his phone and googles the history of the hotel. “Famous for its past connection to the poet Percy Shelley,” he reads. The other lad, distracted by a once-luxurious suite, replies merely “Woah”. “Ozymandias!” Studious exclaims. “GCSE! The Percy Shelley who wrote Ozymandias.”

He doesn’t quote any lines, but he doesn’t need to: it’s in the room now, that desolate image of a desert traveller stumbling upon the trunkless stone legs of the ancient world’s most powerful ruler. Our fresh-faced explorers hit upon old truths too as they trip the beams of glaring sensors, holding their nerve. It’s in the damp deep-pile carpets beneath their high-stepping feet, amid the swirling dust.

Half sunk a shattered visage lies frowning

Unspooked by the screaming alarms and waiting constables, Studious sits at the hotel’s piano and fills the place with music one last time. The ghost-owner would loathe this scene, the youths’ profitless curiosity, their daydream into his domain, and specifically their lack of fear. At last, words appear, his legacy becomes legible. Wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command. This is all that’s left for him to be: the leaver of ruins, since only ruins can make us tremble at how terrible he must have been. Listen, the alarms have stopped – nothing beside remains, but what’s that faint croak?

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

For this and other biographical details I am indebted to Nicholas Van Hoogstraten: Blood and Retribution by Mike Walsh and Don Jordan (Blake Publishing, 2004)

Great piece of writing, David. I'd quibble with the individualised idea of hucksters delivering Brexit or MAGA; I'd say that masks the structural tendency of each that needs to be undone, and the front men as symptoms not causes. Also if you haven't read Dead Souls by Gogol you absolutely should; because it is wonderful but it also includes the most perfect page or so as we arrive at an old estate and Gogol describes that aesthetic of grandeur falling into the greater planning of nature.

Wonderful piece. Thank you. I interviewed him face to face for The Independent in 2000, at the hotel in Hove, and have often thought of him since. Your writing captures the situation superbly.